How to Choose the Right Propeller

Propellers seem like a pretty simple part of your boat, right? They spin, you go. But there’s a lot more to props than what meets the eye. Having the best prop for your boat will improve handling, maximize speed and efficiency and put your powerplant under minimum stress. Run with the wrong prop and you’ll burn more fuel while going slower and possibly even trash your motor.

Caveat Emptor

First, don’t assume that the builder put the best prop on your motor. Manufacturers usually have to go with the prop that’s best for the most diverse applications. They never know if that 250-hp mill will be hung on the transom of a bass boat or an offshore center console. Some manufacturers don’t even supply a prop and the decision could be made by a dealer. If you’re running with the original wheel, there’s a good chance you’ll be well served by making a prop swap, unless it was specifically picked for your application.

No Spin Zone

Before you can choose the best prop for your rig, you need to understand propeller basics:

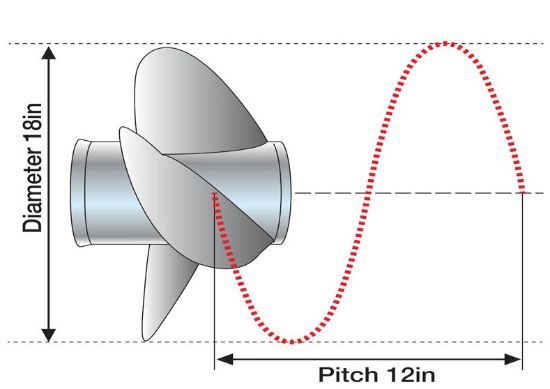

Diameter is the size of your prop, expressed in inches. An easy way to picture diameter is to envision two times the distance from the tip of a blade to the center of the hub.

Pitch is a theoretical measurement, describing how far the prop will move forward through the water with one full revolution.

Cup is the curvature at the trailing edge of the blades. Adding cup to a prop generally increases its bite on the water, reducing slippage.

Blade area is the surface area of each blade in square inches, multiplied by the number of blades. If a prop doesn’t have enough blade area, thrust is lost.

When you look at or consider purchasing a prop, you’ll see them identified by pitch and diameter, expressed in inches. A mid-range outboard prop on a small center console or bay boat, for example, might be identified as a 17” x 19” prop. The 17” is the diameter and the 19” is the pitch. Increasing pitch by an inch usually results in a drop of about 200 to 250 rpm at wide-open throttle. A cupped propeller of the same pitch and diameter will also draw rpm down by 200, as compared to a prop with no cup.

Right Amount of Blades

How many blades should a prop have? Theoretically, one blade is best — it has the least amount of drag and no other blades disturbing the water flow. But making one blade balanced is like trying to walk with one leg — it can’t be done. Two blade props need oversized blades to create enough blade area for effective thrust, and that creates excessive drag and or vibration. So, most common props used for today’s power plants have three blades, which offers the best compromise between balance, efficiency, blade area, and vibration.

Four-blade props are popular on boats which often encounter ventilation issues, such as tunnel hulls and powercats. They usually get a better bite on the water while three-blade props may slip too much. The extra blade can also improve hole shot and reduce vibration. Top-end, however, is usually cut by a couple of mph, as that extra blade also adds drag. Props with fewer than three blades are reserved for applications, such as sailboat auxiliary motors and electric trolling motors. Five or more blades are only commonly used on props for large vessels or special applications.

Prop Material

The material a prop is made of also affects performance. Aluminum props are less expensive than stainless steel props, but they flex more. Usually, top-end speed is a mph or two less than it would be with a stainless prop. But there is an upside to aluminum. If you strike an object at high speed, the softer metal will bend more easily. It is also much cheaper to repair.

Hit something hard with a stainless prop, and often the first thing to give way is part of the drivetrain.

Nibral — a nickel/bronze alloy — is only commonly seen on larger props, for boats in the 35’ and over class. There are a few composite props, too, which are usually inexpensive but don’t perform quite as well as metal props. Since they are so light, however, they make excellent spare props.

How are your Wheels Turning?

How can you determine if your boat needs a prop swap? The most effective method is to look at maximum throttle rpm and make sure it’s in the middle of the manufacturer’s recommended range.

If you have an outboard rated to turn 5500 to 6000 rpm, for example, and it turns 5400 or 6100 rpm, you have a problem. Let’s say you have a 21’ bay boat powered by a 200-hp outboard rated to turn within this range. With your usual load of gear, fuel, and passengers, at WOT it turns 5400 rpm. Top end is 40-mph. At a 4000-rpm cruise, you make about 35 mph. Your outboard is working harder than it should, and its lifetime may be reduced significantly.

But don’t blame the dealer or manufacturer. They, like most, probably put on a prop that spun up the proper rpm when the boat was field-tested before being sold. That was before you filled the tanks, put in your cast nets and safety gear, the anchor, and so on. Maybe you painted the bottom, too, or even added a T-top. Now, in real-world conditions, the original prop isn’t proper.

Swap it out for a prop with an inch or two less pitch, and rpms will be in the recommended range. You should see an increase of speed at cruise of about one mph and about two mph at top-end. At the same time, your fuel efficiency is likely to improve.

Now let’s say that same boat is spinning 5750 rpm at WOT — right where it belongs, in the middle of the manufacturer’s recommended range. You take the boat onto shallow flats quite often, and sometimes getting onto plane during low tide is challenging, so hole shot is an important feature for you. Maybe your prop is just fine as it is, but if you swap it for one that’s cupped, or one with an inch less pitch, or a four-blader, you’ll probably discover that hole shot is noticeably improved.

On the flip side, let’s say top-end speed is the most important feature for the way you run your boat. In this case, adding an inch of pitch will bring your top-end speed up by a mph or two. Will hole shot suffer? Yes. As with most things regarding boat performance, this is a trade-off.

Other Reasons to Change

Why else might you want to change props? If your motor over-revs from ventilating, going from a three to a four-bladed prop will often solve the problem. If you want to increase both top-end and cruising speed immediately, changing an aluminum prop for a stainless one will do the trick. And if you want to reduce vibrations going from a three to a four-blade prop will make a noticeable difference.

Another reason you might want to consider changing a properly sized prop is if you run a dual-use boat. If, for example, the kids want to go water skiing from your center console — which is propped for the best cruising speed, but as a result is slow to get on plane — you may want to swap for a prop that will provide a better hole shot, when you plan to spend the day water skiing.

In any case, whenever you buy a new boat you should plan on trying several different props to find the one that best fits your boat and your needs. If you’ve never played the prop-swapping game, you might discover that you can give your old boat some new life.