What Drives Old Boats to the Graveyard?

Fiberglass hulls may more or less last forever, but generally speaking, as a boat ages, it often becomes less and less functional – until it’s officially deceased. This is particularly true as a boat’s age becomes measured by decades as opposed to years, and there are a few significant forms of age-related structural failure which can end a boat’s useable life. Find out what can effectively kill a fiberglass boat for good.

Hull to Deck Failure

Owners of old boats must remember that fiberglass didn’t start becoming a common boat material until the early 1960s, and some boat builders were slower than others to start building boats right. And, here is where the problem lies – some brands built before about 1990 did not have proper hull-to-deck joints.

Some boats, including several popular-brand sailboats had decks attached to their hulls using metal fasteners through a shoebox design. With age, the fasteners corrode, and UV degrades the exposed fiberglass. Then, it is just a matter of time, and a little challenging use, and the two moldings easily part.

Sailboats are particularly vulnerable to this problem unless their hull and deck were adequately glassed together. One builder we recall in the early 1970s was connecting its decks to its hulls with an extruded aluminum H section in which the deck and the hull edges fit. Screws were put through the H section and if lucky, through a bit of the fiberglass as well, as intended.

One of these boats went down in a storm off Cape Hatteras in the early ‘70s when the stress on the shrouds bolted to the deck simply ripped open the hull-deck joint as the rivets popped out. When the well-known builder of that boat was confronted with the Coast Guard report on the incident, he said he knew nothing about it. Many of these boats are still around and should only be used as day sailors in good weather.

Some high-performance boats had hull to deck problems of record, in the ‘70s, but usually, these were garage brands. By the ‘80s these boats by well-known brands were generally glassed adequately between their hull and deck.

Since the 1990s, virtually all builders have used a chemical bond between the hull and deck that is stronger than the fiberglass itself. It is a lot easier and cheaper to apply than a proper fiberglass joint, so it considered best practice. The best builders use the chemical bond, plus fiberglass and mechanical fasteners.

The toughest part of locating deterioration in a hull-to-deck joint is the fact that it’s often difficult to see. You can usually get an eyeball on the joint by inserting your head into an anchor locker if there’s one with a big enough opening, or it may be visible from the bilge when you look up and to the sides. But it’s rare to have visual access to the entire joint, all the way around the boat.

If the boat’s seam has been glassed on the inside, the joint should hold in all but the worst conditions. For boats not glassed on the inside, the only sure way to check it 360-degrees around the boat is to remove the rub rail. Then, you can replace any suspect-looking fasteners and seal any gaps or questionable looking seams with a sturdy adhesive-sealant.

Stringer and/or Bulkhead Failure

Stringers and bulkheads make up the strength-giving skeleton of your boat. But with age there can be issues with separation from the hull, cracking and/or fracturing, and in the case of wood-cored stringers, rot. The good news is that all of these issues can usually be spotted with a visual inspection. That includes rotted coring because if the boat’s been used at all with rotten stringers, significant and visible cracking will almost surely have resulted.

If your old boat or the boat you’re looking at to buy has bilge access, in all likelihood you can get to see the stringers from there. Use a flashlight and look closely at where the hull and bulkheads meet. Hairline cracks are to be expected, but anything big enough to slip the edge of a dime inside of is a sign of trouble.

In some cases, slapping an eyeball on all of the stringers and bulkheads won’t be easy. You may need to contort into a tight compartment or even remove a section of deck but getting a visual is imperative is assessing how age has treated the structure.

What if you can see an area where the stringer has separated from the hull? The boat is unsafe and needs to be taken out of service immediately until some major repairs can be done by a pro.

Deck Destruction

Any boat built with a plywood cored deck will probably need to have it cut out and replaced at some point in time. Yes, there is pressure-treated plywood with a lifetime no-rot guarantee. But even some of those materials can be problematic if they absorb water, flex, and delaminate from the fiberglass. Plenty of boats get 20 or even 30 years out of a plywood-cored deck, but sooner or later there are almost sure to be issues.

There are two fortunate aspects to rotting, delaminating decks, however. First off, they’re pretty easy to spot. Just walk all over the boat, and if the deck feels spongy or springy anywhere, it’s on its way to needing replacement. Second, cutting out and replacing a dead deck isn’t a massive job. In many cases it may cost no more than a few thousand dollars to re-deck an average 20-ish foot boat.

Finally, don’t be put off guard by a life-time warranty against marine plywood rot. This is not a warranty against soaking up water and becoming soft and spongy.

Transom Problems

Probably the weakest area of a small powerboat hull is its transom. Years ago, it was just a matter of putting in a couple sheets of plywood cut to fit, glassing it over, then drilling through it for fasteners, sterndrive cutouts, tie-down pad eyes and exhaust pipes. This is the first place we’d look for trouble in an old powerboat.

To inspect, remove the bolts or sterndrive collar to get to the core of the transom. Is it damp? Can you stick a screwdriver in it? Has it delaminated from the fiberglass it has been encapsulated in? Answers to these questions will let you know what to do next.

Balsa Core Bottoms

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, one of the best sailboat brands build was made competive by keeping the boat light. It was light because its bottom was laminated with end-grain balsa core. Only trouble is that this builder – and most others at the time – did not realize that fiberglass and the gel coat over it were susceptible to hydrostatic water osmosis.

The result was that 10 years later when these boats were hauled for bottom repairs or new through-hull fittings, it was discovered that their balsa cored hulls were full of water. The chief problem with this was that their boats had become heavy, and so they were no longer quite so competitive in the Wednesday night club races.

Hull Blisters

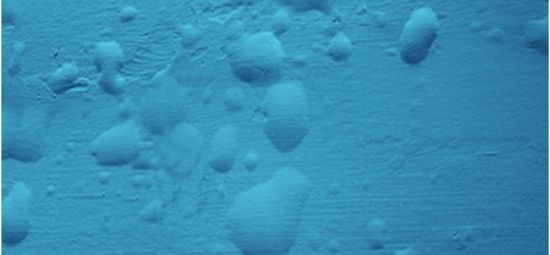

Hull blistering came to light in the 1970s and for years no one could figure out what caused it and why some boats got them and others did not. The blisters were pretty much indiscriminate infecting both cheap boats and expensive ones.

The culprit, again, was water osmosis. Water would migrate through the gel coat, get between in and the fiberglass layers underneath, and cause a blister. With time these blisters could pit the hulls, slowing them down, and sometimes degrading a patch of the bottom.

The solution was for builders to switch from the relatively inexpensive polyester resin it was using in boat hulls to far more expensive vinylester resin – which is impervious to water. Builders began catching on in the early 1980s, and slowly builders started laying up the outside layer of glass mat under the gel coat with vinylester resin.

Voilà! No blisters, no water migration! Now, balsa core could be used in hulls to make them light without worrying about soaking up water. Currently, every name builder uses one to three coats of vinylester resin in the laminations of their hull. A few high-end builders make the whole boat out of vinylester resin. This is why most builders will now give a five-year anti-blister warranty.

Since each boat brand began the vinylester skin coat process at different times, it is hard to know if any given brand had done it by a certain year. The best brands were certainly all doing it by 1990, and when BoatTEST started testing boats in 2000, every boat tested used a vinylester skin coat.

Through-Hull Fitting Failure

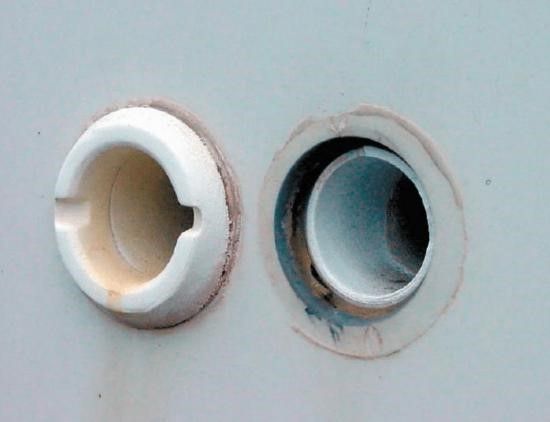

Though both metal and modern plastics certainly can and do fail, (accidentally stepping on a seacock usually does the trick) through-hull failure is more often a problem with boats built with plastic parts during the late 80s and the 90s.

Some of the plastics used through this timeframe were more susceptible to UV damage over the long-term than expected, and they turned brittle with age. The plastic can deteriorate without any real visible damage, except perhaps a color change. Yet, it would snap or crumble with minor contact. Once this deterioration occurs if the through-hull smacks against a piling or drags against a trailer bunk, it can shatter or crumble to bits.

Check for through-hull deterioration by looking for significant color difference between the outside and inside of the through-hull. Cracks are obviously also a reason for concern. When in doubt, you can test the plastic by giving it a mild rap with a hammer or the handle of a screwdriver and see if it stands up to the impact.

Backing Plate Problems

If you’re looking at a boat that was well-built in the first place, it’s likely to have pre-tapped aluminum, phenolic (composite), or starboard-backing plates. If it was really well built, the plate was laminated right into the fiberglass. But quite commonly, a faster and less expensive way to back a cleat or a rail is to use regular old wood. And again, the stuff rots.

Any hardware that’s lacking a backing in good shape should quickly become apparent since it won’t be secure any longer. If a cleat moves when you kick or shake it, something’s obviously wrong. And in most cases fixing the problem is quite easy: just pull the bolts securing the hardware, add a new backing plate, and you’re good to go.

50% of the used boats on the market today are over 20 years old. That means the best used boats to be looking at our 1999 or newer. The older they are, the closer they are to the graveyard -- and for good reason.