Safer at Sea

There are varying opinions on the amount and type of safety equipment and procedures on the water but one thing’s for sure: you can always be safer. All of the points outlined below need to be customized to the size and type of your vessel, your cruising grounds and your experience, but they’re a good start to thinking about some of the right things.

Five Areas to Inspect

The best prevention is preparation. Keeping your boat’s equipment in good working order may stave off catastrophe as well as discomfort. Annual or pre-departure inspections of certain areas and systems will save money and headaches.

Ground Tackle

Spend some time on the bow and inspect what could be your cheapest insurance – your ground tackle and windlass. Look at the top and bottom of your bow roller(s). Do they turn? Are there any cracks in the surrounding structure? Check the anchor shackle to see if it’s still wired shut and inspect the swivel to make sure it turns freely. Test the windlass: take off the cover, check the pawls, lubricate necessary points and lay eyes on the wire connections. Inspect the chain and its connection to the boat. If the exposed end looks sketchy, consider cutting off a few feet. If you carry a stern anchor, dig it out of the lazarette and check it as well.

Steering System

There are few quick fixes for a steering failure on a powerboat so prevention is key. Inspect the condition of steering cables and their connections. Top up steering/hydraulic fluids. Take a look at the rudders and their posts if hauled out and if you have pod drives, get a professional review before a long trip. Sailboats have manual emergency tillers but few mechanical jury-rigs can handle the torque on large powerboats so test the autopilot because, in emergencies, you may be able to steer with it.

Bilge Pumps

A boat is built of pumps: fresh water, salt water, engine, A/C and others but none are more critical than bilge pumps. Check to make sure your bilge pumps are clean, in good operation and with working alarm circuits. Trace the wiring, test the float switches and carry a couple of spare pumps and switches. European boats are spec’d with manual bilge pumps but that’s a rarity on powerboats built elsewhere so carry a portable manual pump or have plenty of buckets.

Engine Room

The engine room will take the longest to inspect because there are so many systems to review. Start with hoses, which should be double-clamped. Wipe them and smell the rag to check for leaks (good fire prevention). Test the tension on the belts, the condition of the diesel fuel (add treatment if necessary), and look for loose or corroded wire connections. Test alarm and shut down systems on the genset and the engines. Check the condition of the raw water strainer, baskets, and gaskets. Make a list of all the fluids you need including steering, transmission, stabilizer, engine oil and coolant, refrigerant, and whatever else. Flush the cooling system and inspect or preventively replace impellers.

Set aside time for the batteries and switches. Inspect the terminals and posts for corrosion and clean them. Make sure the batteries are secured and can’t move. Top up with distilled water if they are wet cells. Check the shore power cord and inlet, all wiring for chafe and your supply of spare fuses.

In reviewing your fire plan, learn how many and what kind of fire extinguishers are required by the Coast Guard for your class of vessel, and then double their number. Check the extinguisher expiry dates and pressures annually. Instruct all crew in their use – pull the pin and aim at the base of the flames. Keep automatic engine room suppression systems in good order. A fire blanket near the galley may help as will baking soda for small fires. Put fresh batteries in smoke detectors.

Thru Hulls

Finally, you already have large holes in the boat that need inspecting. Failed thru-hull fittings can spell disaster so checking and/or replacing them on your next haulout is good preventive maintenance. Check for cracks, leaks, and corrosion. Work the handles on the valves to make sure they don’t stick and you can get them closed in a hurry. Keep an appropriately sized wooden plug tethered to each handle and a mallet nearby to drive the plug into the hole in case a seacock fails. Forespar sells small foam cones that may be used instead of wood and can plug an irregularly shaped hole. Make a drawing or list of where all the thru hulls are located including ones used for the engines, heads, refrigeration, A/C units and more.

Six Must Have Items

A comprehensive list of onboard safety items can get long and much of it will be dictated by Coast Guard rules. But besides the mandatory fire extinguishers and life jackets, and the obvious fixed VHF radio and GPS chartplotter here is some must-have equipment you’ll want aboard.

Medical Kit

Adventure Medical Kits (sometimes private-labeled by West Marine) provide comprehensive and easy-to-use medical supplies that come with a well-organized manual for mountaineering and marine emergencies. Read the contents list before springing for a larger, more expensive kit. For longer voyages, your doctor may put together a customized kit including your personal meds that should be packed with their original prescriptions, especially if you’re crossing borders. If you or one of the crew has a tricky ticker, consider adding an automated external defibrillator (AED). Most models now are under $1,000 and require little training to use.

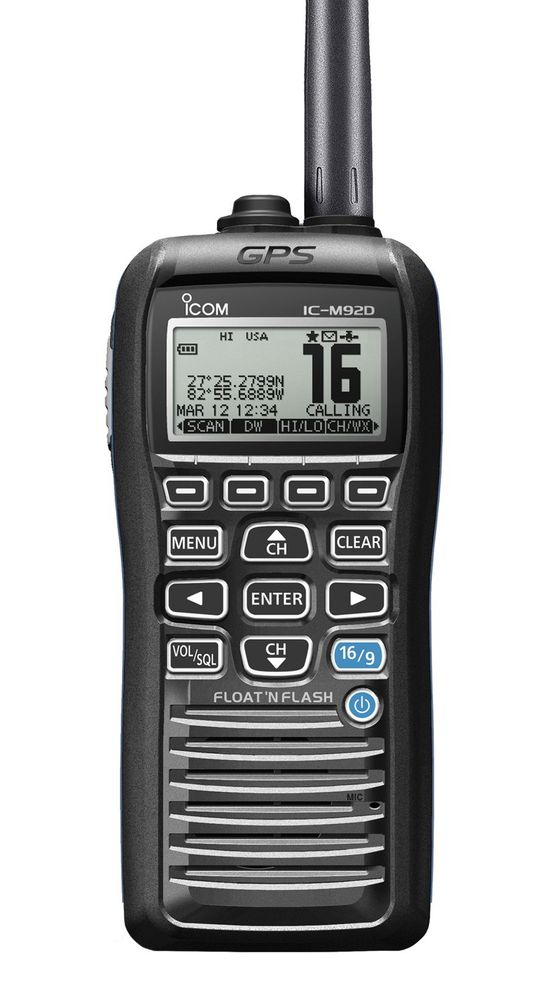

Handheld VHF and GPS Units

In case of onboard electrical failure or if you have to abandon ship, handheld communication and navigation equipment will be needed. Portable VHF radios and GPS units are affordable and easily stowed so have at least a couple of each as backups. Some units are waterproof and float. Also, have a variety of batteries of various sizes for these items (VHFs may have proprietary types) as well as for flashlights and headlamps.

EPIRB and PLBs

Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons (EPIRBs) and Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs) help locate a vessel or crewmember in distress. These devices interface with the worldwide service of COSPASS-SARSAT, the international satellite system for search and rescue (SAR). Registration is free and there is no subscription or annual fee for either. EPIRBs operate on 406 MHz, are waterproof, float and some even have a built-in GPS, making them GEPIRBs. They are registered to the vessel. PLBs on the other hand, are registered to a person. They function much like EPIRBs but are about the size of a smartphone and are usually attached to life jackets for when people fall overboard or abandon ship.

Inflatable PFDs and Harnesses

The Coast Guard specs the minimum number of life jackets or personal floatation devices (PFDs) for your vessel. However, these are often uncomfortable. Inflatable PFDs can be worn for longer periods and with less hassle because they stay compact until they get wet in which case they deploy. Check the expiry date on the CO2 cylinder and have a re-arming kit handy. Consider adding a whistle, light or strobe, highly-reflective SOLAS tape, a harness tether, and a registered PLB to each before a long journey.

Signaling Equipment

The Coast Guard has rules about the kinds and number of flares a vessel of a certain type must carry so these are a given. Most flare kits will also supply a metal signaling “mirror” and a gun to shoot aerial flares. Add a strobe light, foghorn, and a powerful laser pointer. These pointers can be better directed than flares at ships at night, have a long range, and cost around $100.

Liferaft and/or Dinghy

For offshore or long coastal voyages, carry a life raft. Many brands are available but be sure to spec the size (depending on the number of crew – bigger is not always better) and the type (offshore or coastal – they’re different in construction and equipment). You can choose an automatically deployed system mounted on deck in a hard case and cradle, or a portable version in a soft-sided valise. Although it’s an item you pay for dearly but hope to never use, don’t skimp. A dinghy is not a substitute for a life raft but it’s a way to stay dry and floating if the ship goes down. Make sure it’s inflated and has the plugin before each departure because it may turn out to be much more than your tender.

4 Procedures to Practice

In the event of a true emergency, calmer heads will prevail and creating a course of action will make all the difference. Have a plan for various scenarios prior to departure and discuss it with all aboard. Once you’ve practiced, it will be easier to take the right steps if panic sets in.

Emergency Communications

Getting help is a matter of communication. Train everyone aboard in the use of the vessel’s communications equipment including VHF and SSB radios and possibly a satellite phone.

If a problem develops in near coastal waters, call on VHF channel 16. Speak slowly and clearly. Remember the 4 Ps of information to convey: Problem (the nature of the distress), Position (GPS coordinates or location description), People (number, ages, health issues), PFDs (put them on).

When panic sets in, people can forget to provide a good location or misread their GPS position so teach everyone which are the key numbers. If the situation is dire, call May Day three times, wait 10 seconds and repeat. Have instructions near the radio on how to call for help in case the one calling is not trained. A common mistake is waiting too long before contacting the Coast Guard, so if in doubt, make the call.

A Digital Selective Calling or DSC-enabled VHF radio is key. If you can’t make a call, push the DSC button on the VHF to start a relay from vessel to vessel to land unit until it reaches the Coast Guard. Get a nine-digit Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI) number used to identify ships. This will tell the USCG which boat is broadcasting and who to reach. The MMSI is free and easy to get on NavCen.USCG.gov.

Crew Overboard

Man overboard (MOB) is a frequently discussed emergency procedure and the key is to make sure everyone knows the steps to recover crew from the water because it may be the captain who goes in the drink.

First, shout “man overboard” to alert the crew. Stop the boat to prevent getting any further from the victim and toss a life buoy or floatable PFDs in their direction. Press the MOB button on the GPS to mark the position and designate someone to point at the MOB and count, never taking their eyes off the victim. The counting helps you keep track of roughly how much time has elapsed since the event and how far you may have gotten from the victim. If this happens at night or you lose sight of the person, send a DSC distress alert and a May Day. Use the track on your GPS to double back or learn the Williamson turn if track is not available.

Recovery procedures depend on whether the victim is conscious and moving about or somehow incapacitated. Attitudes differ on whether you should approach the person in the water from windward or leeward: From windward, you can drift down on them and block the effect of wind and waves with the boat, making a calmer environment. However, the boat could roll and hit the person so the approach may be better from leeward. The procedure will be dictated by the conditions and the crew that is available to assist. Form a plan to hoist the victim onto the swim platform in case they can’t use the swim ladder.

Fire Suppression Strategy and Tactics

Fire aboard can spread quickly and be devastating within minutes. Per Boat U.S. statistics, roughly 40% of fires are related to AC and DC electrical systems, 12% to engine and fuel systems and 20% are in the “other” category that includes the galley.

Starve the fire of fuel or oxygen: Know where the engine fuel shut-off and propane tanks are. Close access doors and hatches to cut off the air. Turn off batteries, unplug from shore power and turn off the main AC and DC panels. Throw burning cushions overboard before the fire spreads and watch for re-flash even after the fire seems to be managed.

Abandon Ship

An abandon ship procedure is not easy to practice but you can talk through it with the crew and simulate the actions that would need to be taken. Here are 15 steps to review so everyone knows what to do.

1. Put on PFD

2. Note position

3. Call on VHF channel 16 or on SSB - push DSC on VHF

4. Activate EPIRB and/or PLB

5. Coordinate/count crew and assign tasks to keep everyone functional and calm

6. Collect abandon ship bag and supplies on deck

7. Launch life raft and attach to leeward side of vessel so it doesn’t become entangled

8. Launch dinghy and attach to life raft

9. Do not abandon ship prematurely

10. Try to stay near where the vessel went down

11. Once in the water, keep crew together (tied if necessary)

12. Assign a buddy system

13. Collect as much debris around you as possible – angular objects like coolers are easier to spot from a distance

14. Fire flares only when there is a chance of being spotted or use a laser pointer

15. Designate a watch-keeper at all times

Five Points of Extra Credit

If you’re going the extra mile (both in distance traveled and effort expended) consider these five actions to enhance your safety and give you greater peace of mind.

Get Training in Basic Medical Care

All crew should have basic medical training. You can opt for one-day classes in CPR and First Aid from the American Red Cross or the America Heart Association as well as from a slew of independent providers. However, be mindful of the fact that these classes are geared toward urban environments where emergency medical services (EMS) are expected to arrive within 10 minutes, which is not the case on a vessel at sea.

For long distance voyages, all crew (usually both parties of a couple) should consider taking a wilderness survival course. This training is significantly more expensive and may require a week of time. Ask about classes that focus specifically on survival at sea tactics because you may need to be your own paramedic.

Carry Supplemental Tracking & Communications Equipment

GPS-enabled tracking devices like SPOT or inReach are affordable position locating and basic communication devices for casual check-ins or SOS messaging. You can send canned messages on SPOT and two-way texts on the inReach but monthly charges apply for both. They are more affordable than satellite phones and EPIRBs but they are not a substitute for either.

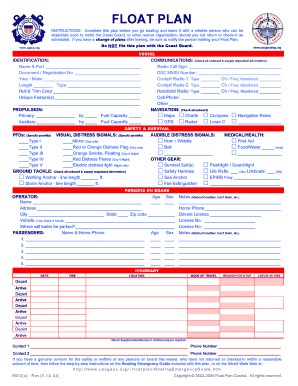

File a Float Plan

File a float plan with a friend, relative or an on-water assistance service like Tow Boat U.S. Include name and type of vessel, point of departure and destination, time of departure and of expected arrival, number of people aboard and their names and ages. You can download a float plan form from USCGboating.org. Here you can also get an 86-page Federal Requirements Brochure, an accident reporting form and general survival tips.

Pack a Comprehensive Ditch Bag

You can Google abandon ship bag contents to get started. However, restraint is key when packing a ditch bag because you must consider where will you store it aboard, the room it will take up in a life raft, its weight and your crew’s ability to get it on deck, and how often you’ll take the time to keep its contents up-to-date. For short coastal voyages, if it’s time to abandon, plan to jump in the dinghy with at least the VHF and cell phone in a dry bag, PFDs, flares, waterproof flashlight, and your personal and ship’s documents.

Prepare Paperwork

Speaking of documents, having your paperwork in order and easily accessible is key to a quick or unplanned departure or being boarded by authorities. Keep the following at hand in one dry bag: vessel documentation, insurance, cruising and fishing permits, and any necessary entry documents for foreign countries. In the other dry bag, keep passports, credit cards and crew information including medical needs.