Access More Boat Tests

Already have an account? Login

Bruce King Designed Whitehawk

Whitehawk was built in 1978 to a Bruce King design. King was a hot yacht designer in that era and was most famous for the line of Ericson fiberglass cruiser/racer sailboats which he had designed. Whitehawk was built in Rockland, Maine, at Lees Boat-shop by O’Lie Neilson, and at the time was the largest vessel ever built with the West System product using the cold molding process. West System was in its infancy. In fact, Whitehawk was one of the largest boats built in America in that decade of any material, and preceded the era of megayachts by a few years.

Origins of her Fame

Because she was so large, and because she was built all of wood in an age of fiberglass, she caught the eye and imagination of the boating press, and a number of articles were written about her. Month after month, the yachting magazines chronicled her build progress until her launch in 1978. As a result, generations of yachtsmen have followed her ever since, and she is one of the most famous sailing yachts in America.

Genuine Tree Wood

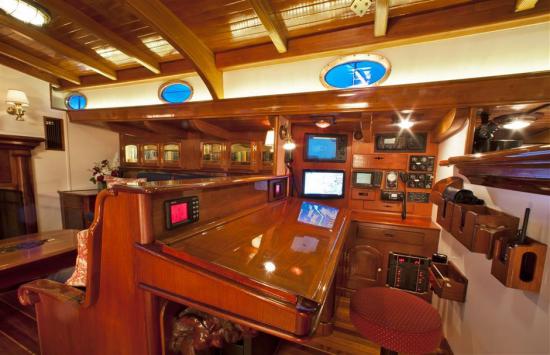

She was designed like a classic wooden yacht with all of the brightwork and luxury details that would have pleased the Astors, Morgans, or Vanderbilts. On deck and below she looked and was built very much like yachts or yore. But her hull was different. It was built with a new process of cold molding that lightened the boat somewhat and made her more seaworthy at the same time. This process was popularized by the Gougeon Brothers and their development of the West System of epoxy/wood construction in Whitehawk was the proof of concept.

Rather than being built in the conventional manner of planks -- that had to be caulked and nailed to heavy frames every few feet or so -- cold molding involves strips of epoxy saturated wood laid over a jig that formed the hull’s shape. The epoxy not only glued the wood together, but it also created an impenetrable barrier to water. It was a radical idea at the time, but it turned out to be a good one and the West System continues to be a popular method of wood construction.

Topside Finish. Triple-planked cold molding with epoxy eliminated the need for many frames, which lightened the boat and also made her hull more puncture-resistant. With the elimination of most frames, more livable room was created inside of her 20’6” (6.25 m) beam. Her exterior surface was faired and then painted. In one of her recent refits, her hull was covered in Alexseal, a premium polyurethane topcoat technology that employs UV absorbers. The result is a glass-like finish with high gloss. We had the opportunity to inspect her hull from the waterline to her rail both from the ship’s tender and when swimming around her, and can report that her topside finish is flawless.

Her Keel and Centerboard. Whitehawk draws 7’6” (2.28 m) which allows her to sail into many places where a sailboat of this size might not be able to enter, thanks to her stainless steel centerboard. It increases her draft to 15’ (4.57 m) and improves her performance to windward. The hydraulic centerboard has holes in the bottom so it fills with water when deployed. The combination of her cold molded hull and her centerboard make her relatively fast off the wind, and while she is by no means a down-wind sled like a Bruce Farr design, she is nevertheless competitive on the classic yacht regattas that she enters most years at venues from Antigua to Nantucket.

Built for Offshore Cruising. She displaces something on the order of 82 tons, which makes her a substantial yacht, and means that it takes a bit of wind to move her briskly. This makes her ideal for offshore work and, indeed, on her delivery last winter from Newport, Rhode Island, to Antigua, she saw winds up to 35 knots in the north Atlantic and a speedy passage south. During our own sail south of Antigua, she handled winds from 15 to 25 knots (30 knots in squalls) on a close reach with ease, and we recorded speeds up to 11.3 knots. Between the islands, seas often grew from four to six feet and Whitehawk rode over them in comfort – something that can only be enjoyed in a large, heavy sailboat with a 20’6” (6.25 m) beam.

New Owner and a Major Refit

Whitehawk was purchased eight years ago by a well-known East Coast yachting couple who have a particular love of old, classic wooden boats. They, in fact, have been major benefactors of the International Yacht Restoration School (IRYS) in Newport, Rhode Island, for the last two decades. In hindsight, Whitehawk could not have had more caring, or better, owners. They have spared no cost in improving her, refitting her, and making her be all that she could be.

Major Refit. After purchasing her, one of the first things the new owners did was take her to Lyman Morse in Maine for a major refit in 2010-11. There, she was ensconced in her own all-weather shed. Her old deck removed and a new teak deck laid down, a major undertaking on a deck that was never intended to be removed. Her cockpit was refurbished and her 10-sided Mandala skylight was reworked to stop it from leaking. Huge, electrically-powered sheet winches were added to make sail handling easy. Powered halyard winches were also installed that meant the vessel could be sailed easily by a crew of three.

New Sail Plan. At Hinckley Yachts in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, both her mizzen and mainmast were shortened and re-tapered and new lighter rod rigging fitted because she had always been a little too tender. Taking over 4,000 lbs. (1,814 kg) out of her rig-plan was a major improvement to both her handling and her performance, as she still has plenty of sail for light air. A new asymmetrical chute for off the wind work adds speed never possible before downwind even with the taller masts. And in heavy air, she lost no speed, because with a double-reefed main she stands up nicely on her lines, where she was intended to sail. By cutting down the masts and installing new rod rigging, the vessel became easier to handle and even faster in a blow. We can attest to that on our test run.

Sailing Down Island. As noted above, we sailed her in winds from 15 to 30 knots for six days and not once did she have her rail in the water. Most of the time we were on a close reach, but we also had some legs that were a beam reach, as well as hard to windward. She consistently sailed on a close reach from 9 to 11 knots, depending on the wind speed, and our fastest speed was 11.3 knots hit on a particularly blustery afternoon between islands when a rain squall blew through. (We should add that all companions were cozy and dry behind the yacht’s dodger in the cockpit, and only the helmsman got a little wet – and he loved every moment of steering the 105-footer through the six-foot seas in a blow.)

Sail Handling. Her main and mizzen are conventional rigs, but with halyards and sheets handled with powered winches. Her mainmast has running backstays and they are led to the manual winches. On our sail, the port running back never had to be adjusted. Her headsails are both roller furling with hydraulics making the chore easy and fast. We found that it was particularly easy to shorten sail when squalls blew through, by simply rolling up the headsail a bit. Then, letting it out once more the squall had passed. The vessel also has a roller-furling staysail, something we never needed to use, thanks to the breezy conditions. Even with two reefs in the main, the sail is enormous, but lazy jacks aided in dousing the sail. All sails were Spectra made by North Sails.

Engine Room Details. A CAT 3126B 370-hp diesel engine powers the hydraulically actuated prop which can drive the boat at 9 knots. Since we had wind every day, the engine was just used to get us into and out of harbors and to find a place to drop the hook. There is a bow thruster available when maneuvering in a marina. The boat is also equipped with 20 kW Northern Lights generator which was more than enough to handle both the watermaker and the AC when underway. It also kept the ship’s batteries topped off for plenty of power when at anchor to run all of the electrical appliances, including hair dryers and the ship’s wonderful Headhunter toilet system, while at anchor with the generator off. The 1,080-gpd water-maker was run during the day when needed. Because of its capacity, it only needed to run a couple of hours a day to keep the water topped off. The cooktop is gas, and the oven electric, which keeps the need for a generator minimal.

Tankage. Whitehawk carries 830 gallons (3,141 L) of fuel, quite a bit for a sailboat of any size, and that is enough to power her through a mid-ocean doldrum. She reportedly has a range of over 600 nautical miles at 9 knots, so at six knots she should be able to push 1,000 nautical miles on a load of fuel. She also carries 655 gallons (2,479 L) of fresh water, an amount unheard of on virtually any large vessel these days. Again, she is designed for long-distance cruising. In addition to the reverse-osmosis watermaker, there is an extra filter for a special drinking and cooking water faucet in the galley. The water aboard Whitehawk was undoubtedly better than any to be found ashore (virtually anywhere).

Observations

Before departure from Antigua, we walked the docks of English Harbor and looked at the sterns of dozens of very large sailboats – 120’ to 200’ (36 m to 61 m). All were built of aluminum or steel, with sterile decks, and no particular personality or style other than just simply being “big.” Not one had the charm, the graceful lines, or the beauty of Whitehawk.

We were surprised as we sailed the 190 miles from Antigua to St. Lucia at how many times boaters in other vessels, both power and sail, came over to us to take pictures and shout their good wishes, usually with the word “beautiful” somewhere in the greeting. We suspect a more jaded and experienced group of boaters couldn’t be found anywhere in the Caribbean, yet the unmistakable classic lines and execution of Whitehawk set her apart from the other sailboats -- and motoryachts -- many far larger. It reminded us that there are still many boaters who appreciate style and tradition over just a raw display of wealth. It is about the appreciation for, and holding onto, an era gone by.

Price

Whitehawk is currently for sale for $3,495,000. Her brokers are Georges Bourgoignie at Fraser Yachts, and Paul Buttrose of Sparkman & Stephens. Georges mobile number is 305-491-2211 in the U.S., and +33-7-77-86-61-78 in Europe. And, Paul’s mobile number is 954-294-6962.