Boat Buying Tips: What Hull Shape is Best?

Overview

The shape of a boat's hull -- the bottom shape -- is determined by how fast the boat is intended to go and in what water conditions. Round bottom displacement hulls are ultra-efficient at low speed, and therefore great for long-range cruising, but have upper speed limits determined primarily by their length, and other factors as well.

Planing boats with angular bottoms can run 50 or 60 knots or more, depending on how much horsepower is available, but are less efficient at low speed. Who cares? For these boats, and for their buyers, it's all about speed.

Most folks want to go fast, so they choose a planing hull. And that's what builders build, too. But all planing hulls are not equal.

“Displacement” Hulls

Describing a hull as "planing" or "displacement" isn't really accurate in the first place. Hulls operate in displacement or planing modes, determined by their speed vs. waterline length. That's the speed/length ratio, calculated by dividing the speed in knots by the square root of the waterline length.

A boat with an LWL of 36 ft traveling at 6 knots is operating at an S/L of 1.0 (square root of 36 is 6, divided by 6 knots = 1.0), which is for most hulls the most efficient displacement speed; it takes very little horsepower relative to weight to push a hull at this speed.

Hulls designed to operate at displacement speeds, below S/L 1.34 or so, have full-bodied hulls with lots of curves in the bottom -- a typical displacement hull looks like an egg cut longitudinally. Displacement-speed hulls don't generate lift as their speed increases, so above S/L 1.34, adding more horsepower doesn't add much speed; it only increases the waves produced by the hull pushing its way through the water, which absorbs most of the energy from the added power. Eventually the bow and stern waves become so large that they stop the hull from moving any faster.

Slow Boat to China. Displacement hulls are for long-distance cruisers with lots of time and the need to carry all their worldly possessions along with them. Today, even many sailboats have hulls with planing bottoms: When the wind is fresh, their skippers hoist more sail and see speeds well over true displacement numbers.

Planing Hulls

Hulls designed for planing have sharp forward sections to cut through the water with minimal fuss, and hard chines (not rounded) and straight, not curved, after sections that develop hydrodynamic lift as power is added. Rather than the hull pushing water aside, it rises and slides along the top until, at S/L 4 or so, the boat is truly planing, the chines and transom running free of the water.

Once on plane, speed is mostly dependent on horsepower and weight. Want to go 50 or 60 knots, or even faster? Dump in more power, get rid of excess weight and hang on.

Semi-Displacement – Say What?

Between displacement speed and planing speed, the hull is said to be in -- you guessed it -- "semi-planing" mode: Not quite planing, but way faster than displacement mode. Most people operate their boats most of the time in semi-planing mode, and some hulls -- "fast trawlers," for instance -- are designed to operate in the semi-planing mode.

To a yacht designer or boat nut there's a world of difference between semi-planing and planing-hull boats, but most people won't see it -- both types have chines and modified V-shaped bottoms. For the boat buyer, the choice is either planing or displacement, and most buyers choose to plane.

Deadrise is Important

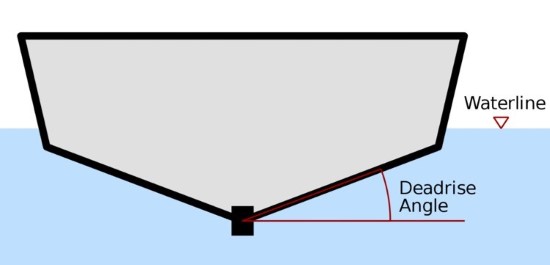

One variable that's easy to see, and one the buyer should consider before choosing one boat over the others, is deadrise -- a most important factor in the bottom design. Deadrise is the angle of the bottom sections relative to a horizontal baseline at the keel -- in other words, it's how sharp the V is.

Deadrise can be measured anywhere on the hull, but in the specs, most builders list transom deadrise. Why? When a fast-moving boat hits a wave and jumps clear of the water, she lands stern-first, on the after sections of the bottom. The right amount of deadrise there, and years of experience show this to be 24 degrees, cushions the landing and makes it bearable for the crew.

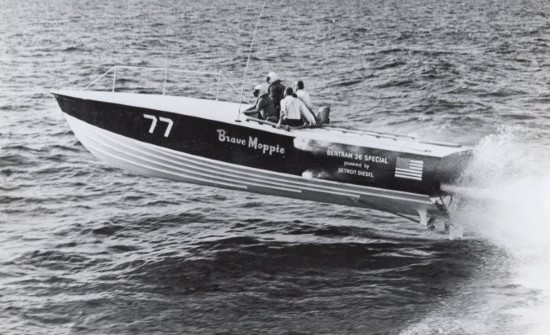

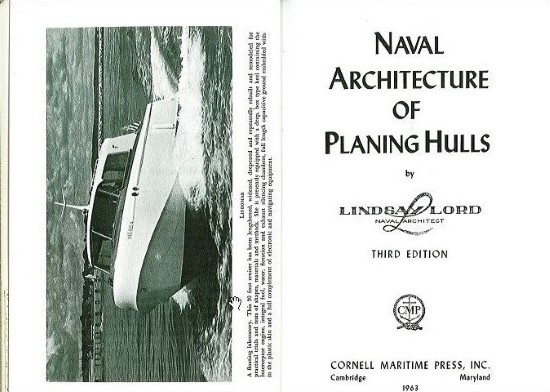

Until the post-World War II years, most planing-boat bottoms were flat, or nearly so, in the after sections. This is great for speed -- flat-bottoms are fast -- but make for a bone-shattering ride in rough water. After studying the research of naval architect Lindsay Lord, and experimenting with many bottom shapes, designer C. Raymond Hunt developed the "prismatic" hull, with a constant 23.5 degrees of deadrise from amidships to the transom.

The Beginning of the Deep-V Era

Richard Bertram built a race boat of Hunt's design for the 1960 Miami-Nassau powerboat race, won the race going away in extremely rough conditions, and the rest is history: This is, essentially, the 24-degree deep-V used by many boatbuilders, and almost all race boats, today.

The deep-V bottom isn't perfect, though, and not all boats have to be deep-Vs. The advantage of the deep-V comes when the hull leaves the water, so boats that don't jump out of waves – for example, big, fast sportfishermen, convertibles, sedans, and motoryachts -- don't need a deep-V; they do fine with a shallower V, and maybe sharper sections amidships to cushion the ride.

Deep-V hulls have less initial stability than those with lower deadrise, and can feel a bit "tippy" under certain conditions, especially in smaller sizes. They won't capsize, but they respond to folks moving around on board. When at rest, or trolling slowly, they can be rolly. Boat buyers shopping for an all-around family boat, one that's good for kids to jump around on while at anchor, for example, might do better with a modified-V hull with less deadrise, which equals more initial stability.

Consumer Caveat on the Word “Deep-V”

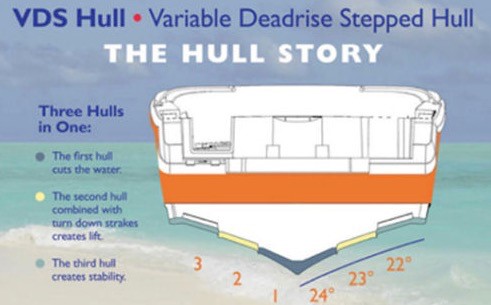

Over the years, most builders abandoned the “constant” deadrise from the midsections aft and “warped” the bottom from a sharp deadrise at the bow to a more moderate one at the stern – say, down from 24-degrees to 17 to 20-degrees, which BoatTEST calls “modified-V” hulls. Some builders call hulls with these deadrises “deep-V”, so consumers should drill down and find out exactly what the deadrise is at the transom in terms of degrees.

BoatTEST considers “Deep-V” hulls to be ones with a deadrise at the transom from 21 to 24 degrees. (Some builders don’t publish the deadrise angle at the transom because they don’t want to get into the debate about which angle is best.)

Many builders have modified the classic deep-V from the 24-degrees precisely because they are rolly, and because they are slower and burn more fuel. Deep-V hulls demand more horsepower than flat- or modified-V hulls to achieve a particular speed. Or, taken another way, the flatter hull will be faster with similar horsepower, or the same speed with less hp, than a deep-V hull of the same weight.

The modified-V boat bottom (usually 17-degrees to 20-degrees at the transom) will therefore burn less fuel, reducing operating costs. It will also go faster with the same power than a deep-V hull – and, it will also roll less. Boats with modified-V bottoms span the gambit from sportboats to express cruisers and even to some motoryachts. These boats are not jumping off waves and they always have their mid and stern sections in the water. They don’t need the cushioning-effect of the deep-V. However, usually their forward sections are quite sharp to slice through the waves without pounding.

So, what's the best hull?

In our opinion, as great as the deep-V bottom is when conditions warrant it – high speed in choppy or rough conditions -- for overall use most folks will be just as happy with a modified-V hull. They will roll less, go faster and use less fuel, and maybe even require a smaller engine.

Offshore fishermen who go out in all weather, high-performance speed freaks, and others who want to go as fast as possible as often as possible should choose a deep-V. Since they don’t care about fuel consumption or anchoring out and rolling, they should preserve their back bones and go deep-V.

Folks who want to take a leisurely bluewater cruise should shop for a comfortable, efficient displacement-hull boat, and find the time to enjoy being aboard. What's the hurry, anyway?

Purpose-Built

Builders design the hull for the task at hand. Generally, we have found that well-known name builders do a good job of matching the bottom shape and deadrise to the tasks the boat was intended to perform and bodies of water where they know their boats will be used. These builders are experienced and have long since buried their mistakes in the past, and have often discovered the right boat bottom for a given application the hard way.

Having said that, we occasionally come across boats that are designed to go 30 knots in coastal work which are a little too full forward, or ones that have a wide chine taken to the stem, and they tend to pound in those conditions. In these cases, bow shape is more important than the deadrise at the transom.

Bay/Flats Boat Caveat

Small, underfinanced, no-or-low-infrastructure boat builders are where most problems we see crop up. The most dangerous boats we have tested over the years have been bay and flats boats. Their builders often encourage big engines, and their bottom shapes tend to be flat and sometimes the hulls have bad habits.

At high speed these boats can easily flip. These builders generally don’t have the resources for proper engineering, R&D, and in-depth testing before the final mold is made. Once they’ve spent their money on a mold, they have a boat that they have to sell no matter what.

We have not covered all hull shapes here, but the above descriptions should indicate what consumers should look for when buying a boat for a specific application.